Audio Interface - Low Latency Performance !

A 14 Year Investigation

The origins of this article is a previously published summary from 2015 of the initial 3 part series I originally posted at my now archived DAWbench Blogsite starting around 2011, when I first developed the testing and reporting procedures. The project and database has been ongoing and maintained across forum threads and social media over the last 14 years, so it’s time to bring it all together here on Substack for a current audience.

Throughout the article I will amend tense for historical context and bring the information right up to date as of 2025. The information and collated data is directly related to Windows, but can be used as a cross reference for MacOS as well, to a lesser degree.

At the time we were seeing an increase in a wide and varied range of audio interfaces available, all with their strengths in regards to specifications and features. The market was becoming crowded with new interfaces all jostling for the same limited space, cramming more and more features at affordable pricing, which on the surface seemed like a win/win for those looking at dipping their toes into the pond, and for many it was just that.

However for those that placed higher demands on their systems, the cracks started appearing very quickly when the interfaces were driven to lower latency. This became more and more important when using things like guitar amp simulators in real time, so in those instances a lot of the gloss of the extra features paled when the performance of the drivers did not hold up to the demands of the low latency working environments that were increasingly required. Now while a lot of the interfaces performed well for the majority in less critical working environments, the performance variables could become quite dramatic at the lower to moderate latencies, and that is what I specifically focused on investigating and reporting on.

Hardware Buffer Setting v Actual Latency.

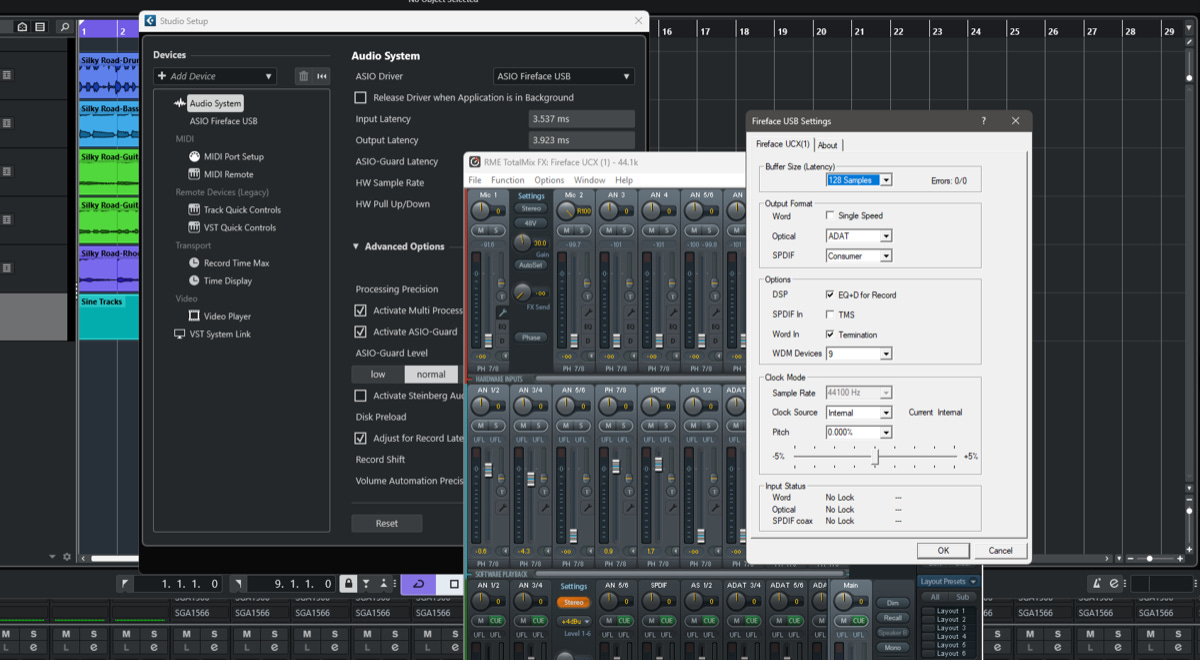

All audio interfaces have their respective hardware control panels where adjustments to buffer /latency settings can be made. The buffer settings in some case have little correlation to the actual delivered latency achieved due to various factors including - added safety buffering for both the Input and Output streams, arbitration delays associated with the FPGA/DSP and Protocol Controllers, as well as non reporting of AD/DA conversions.

Some interfaces even resorted to simply reporting nominal figures, which would compromise the ability of the host DAW's to be able to keep everything in sync due to wide variances between the reported and actual latency.

The variances at respective latency settings was also quite substantial, for example the RTL at a listed 064 setting could vary anywhere from under 4ms all the way to over 12ms , so obviously there was no real consistency in regards to what the actual panel setting represented. To say that there was a wide and varied range of reported latencies across the interfaces is an understatement, quite literally, some of the listed panel settings were little more than window dressing.

To help navigate the minefield I collaborated with Andrew Jerrim of Oblique Audio and assisted him in developing a Round Trip Latency Utility, which allowed me to accurately measure the actual RTL of each respective interface .

Its also worth noting that simply having the latency value available, didn't guarantee that the interface would work reliably at that latency.

Protocols and Driver Performance – PCIe / Firewire / USB / Thunderbolt.

There are various protocols that were utilised for connecting digital audio interfaces to computer platforms, initially PCI/PCIe was the more traditional protocol in the earlier days when studio computing was reserved to larger workstations, and was the most consistent for delivery solid and reliable performance over the competing technologies like Firewire and USB. As the technologies evolved and studio/working requirements shifted to needing more flexibility and/or portable solutions, Firewire and USB/USB2 became more and more popular. This allowed manufacturers to offer solutions that could be used across both desktop workstation and mobile laptop solutions equally. This had now evolved to the point where PCIe, despite still being a solid and reliable choice, was being overtaken in popularity and available interface options by the more flexible protocols of FW/USB/Thunderbolt. How the new preferred protocols faired in regards to comparative low latency performance was the real question, and one that I spent enormous time and energy investigating over the years.

As the testing pool increased it was becoming quite evident that there was a consistency amongst various interfaces from different manufacturers in regards to not only control panel settings and corresponding latency values, but also the comparative performance of the units. It was pretty obvious we were dealing with not only the same OEM hardware controllers, but also baseline drivers.

Trying to get official confirmation of the OEM controllers used was proving difficult so I needed to dig a little deeper with some trusted industry contacts who gave me some clues where to dig and managed to narrow down the OEM FW controllers that were being used. The most widely used FW OEM controller at the time was the Dice range from TC Applied Technologies . The list of manufacturers using the controllers included TC ( obviously ), AVID, M-Audio, Presonus, Focusrite , Mackie, Midas, Allen and Heath. It is worth noting that AVID and M-Audio differed from the other units listed in that they did not use the base OEM driver, instead developing and using their own.

TC Applied was acquired by Behringer in 2015 and ceased supply to all 3rd party manufacturers, so all of the interfaces using the Dice solutions were effectively End Of Life overnight. NFCR !

The second most widely used range of FW controllers was by ArchWave ( Formally BridgeCo) , the list of some of the manufacturers using the controllers included - Apogee, Lynx, M-Audio, MOTU, Presonus, Prism and Roland. The 3rd controller was a joint venture developed by Echo and Mackie which was used in the Echo Audiofire line of interfaces, and the earlier Mackie Onyx rack/desktop models.

The OEM USB2 controller most widely used was (and still is to this day ) XMOS , while some manufacturers were also using a custom FPGA in combination with other 3rd party USB controllers. Base drivers were provided by numerous 3rd parties, CENtrance, Ploytec, Thesycon, and in short, it was an absolute crap shoot. Despite the interfaces using the same OEM controller, performance varied greatly depending on the choice of OEM 3rd party base driver and the added optimizations ( if any ) being deployed by the OEM/manufacturers. 3rd party OEM controllers and associated drivers covered a large % of the FW/USB audio interfaces available, some exceptions were Steinberg/Yamaha, Roland and RME, who developed not only their own proprietary custom FPGA/ controllers in house, but also coupled that with development of the drivers. RME were a stand out not only in the level of development that they applied at both controller and driver level, but also in the level of performance that they achieved across all of the available protocols.

The newest option for device protocol was the one with the greatest potential to equal PCIe level of performance, which was Thunderbolt. Thunderbolt had an interesting early history as it was essentially a copper version of Lightpeak , which was an optical dual protocol external interconnect with dedicated PCIe x4 and PCIe x16 for DisplayPort. This in theory would allow manufacturers to achieve PCIe LLP from an external interconnect, as well as being backward compatible with all other current interconnects running on the PCIe bus - FW and USB2/USB3. Despite the potential advantages it offered digital audio interface manufacturers, it was a slower road in regards to adoption than many had hoped. Some MAC only TB interfaces started appearing on the market and were showing some potential, the adoption on Windows however had been a lot slower.

There have been numerous theories as to the reason for the slow adoption and it was evident that we were not really getting the whole story. There were uploaded videos from an Intel Development Forum in September 2010 ( 6 months before Apple officially released TB ) where there was a proof of concept demo of Lightpeak being used for Professional Digital Audio application by none other than AVID, running Protools HD, using an Alpha/BETA Lightpeak equipped HD I/O on a Compal ODM white box PC Laptop running Windows 7. Videos can be seen Here and Here

In short and from what I had been able to conclude through my own investigation, after the initial exclusivity deal that locked the TB1 protocol to Apple, various other stumbling blocks regards licensing and other overzealous requirements imposed, made it very difficult for developers to invest in R&D. Not to mention Microsoft’s refusal to “officially” support TB2 on Windows 7/8. That’s not to say it didn’t work, simply that it was not officially supported. Microsoft officially supported TB3 only on Windows 10, which was a move in the right direction, but at the time all the current audio interfaces were TB2 which required an additional TB3-TB2 adaptor, and a large % of the end user base were not on Windows 10, so it was still quite a while before TB was more widely accepted on the Windows platform.

The above was mostly compiled between 2011 and 2015, so how much has changed in the last 10 years ?

Protocols in 2025 - Survival of the Fittest, Navigating the New Players !

In regards to protocols, Firewire had pretty much been abandoned by all except for RME after the demise of the OEM Dice chips availability. The RME FW options continued to around 2020 using their own in house controller/driver implementation.

PCIe has still maintained its superiority regards ultimate Low Latency Performance, but only a few companies have maintained any products in that arena, namely Lynx and RME. Also AVID with their aging HDX cards, but they can be considered legacy, as AVID also seem to be trending away to other protocols now with their current interface options. HDX cards have never been party of this work, as they are not focused on native LLP.

In regards to USB, USB2 has cemented itself as a mainstay, and I can safely say that most if not all manufacturers have had USB2 interface options available at some point. We have also had the introduction of true USB3/C devices which offer higher I/O and potential for lower latency. I say true because some of the “USB-C” units are not in fact USB3 devices, but USB2 with a USB-C connector. Don’t get me started on that last point !

For most if not all manufacturers that do not develop their own controller/drivers, the current USB based interfaces on the market are using an XMOS controller in combination with some variant of the Thesycon driver. There are multiple tiers of Thesycon drivers available to developers, but that’s a whole other rabbit warren.

Thunderbolt – Well the question is did Thunderbolt deliver on the promise ?

Well yes and no, depending on which angle you view the perspective from, IMO. There was an initial batch of Thunderbolt 2 interfaces that hit the market from various manufacturers, in no particular order- Focusrite, Lynx, RME, Antelope, Presonus, Universal Audio, with varying degrees of compatibility and performance curves navigated across both platforms. Less so on MacOs, but focusing on Windows, it could be a bit of a minefield depending on the generation of TB controller being used, the O.S revision, motherboard level implementation, and also generation of driver and control applet.

Actual native TB2 controllers were rarer than hens teeth on Windows platforms, I had one of only a handful of controller cards that ever landed in Oz, running on a reference system originally running on Windows 7, yep, you read that right, which then was updated to Windows 10 and a TB3 controller for better (official) compatibility. With the move to a TB3 controller, the TB2 interfaces were then required to be connected via a TB3 to TB2 adapter, which for the most part worked fine , until they didn’t, but that’s another rabbit warren that is not a focus of the article, so I’ll leave that one for another time.

A quick browse of the LLP Database and it is evident that for the most part the better Thunderbolt devices delivered on the promise of near PCIe performance, in other instances they delivered performance nestled in between a bunch of USB/FW devices. So in short, just using Thunderbolt did not guarantee PCIe level performance. It came down to the respective driver development and the quality of the delivery.

The other thing that is interesting and worth noting, is that after the initial rush to develop TB devices, some manufacturers have chosen to not continue down the path and dropped their TB product lines completely, i.e, RME and Presonus. RME stopped at TB2 and never offered a TB3 device, while Presonus did introduce a new TB3 product before EOL’ing the whole Quantum TB line, which has now moved to USB-C. Focusrite dropped their original Clarett TB line of interfaces and moved that to USB2/C, but have reintroduced some Pro Red devices with TB3. Those units however seem more focused on targeting AoIP , which I will get to next. Some manufacturers who have stayed the course with TB are Antelope, Lynx, MOTU and Universal Audio.

It does need to be noted that with the move to USB4/TB4 , compatibility for TB2 units previously using the TB3 to TB2 adapters successfully has ended. TB3 interface cards are EOL and not available for current platforms, so those who have heavily invested in TB2 devices are out of luck moving forward if they want to move to a new computer system, and for some, that is a huge investment that is essentially obsolete

AoIP/Ethernet Audio - This is the newest player that entered the arena , AoIP - Audio over I.P, sometimes referred to as Ethernet Audio, Audio over Ethernet or Network Audio. The 2 main players being Audinates Dante and AVB, the later being developed by IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers). Some would consider the choice as akin to VHS v BETA, but the 2 protocols IMO differ enough in my main area of focus, being studio level LLP, and especially on Windows, that makes the choice easier, well for me at least.

Lets get into some finer detail of each protocol, and cover the main differences.

Dante : Dante (Digital Audio Network Through Ethernet) was developed by Audinate in 2006. As its a proprietary standard, the rights to Dante must be licensed by each hardware manufacturer to be able to be used in their products. The license is expensive, IMO, and is reflected in the higher cost of units featuring Dante capability. Despite the proprietary nature and the additional costing, Dante currently has the widest acceptance in the industry with dozens of manufacturers using their controller and protocol in their products, including Focusrite, MOTU, RME, Lynx, Yamaha/Steinberg, just to name a few.

Audinate also have a Dante PCIe DSP accelerator card that has been utilised by both Focusrite and Yamaha/Steinberg, that lowers I/O and RTL latency to levels in range of some PCIe/TB devices, and makes it better suited to studio production environments, IMO.

They also provide a DVS – Dante Virtual Soundcard using just a standard Ethernet connection, for less stringent latency environments like installation/live. Listed I/O and RTL’s for the DVS is 4-10ms, but from experience the lower latencies are not usable in any practicality under load in a studio/production environment, so safe to say 20ms RTL wouldn’t be a major draw for many in studio environments.

AVB : AVB (Audio Video Bridging) was developed in 2011 by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), which is the same organization that developed the original Ethernet standard. AVB (also known as “IEEE 802.1BA”) has similar specifications as Dante, with a slightly higher inherent latency. Unlike Dante it is an open standard, meaning manufacturers do not need to license the technology. Some companies that offer products are MOTU, PreSonus, RME, Yamaha and AVID.

Unlike Dante, AVB does not have any facility for accelerating the protocol, but it claims deterministic latency of 2ms in their market speak, which to be honest I have never managed to reconcile how exactly that correlates to actual I/O and RTL, as in the same articles I have read where those numbers are quoted, Dante is claimed to have as low as 1ms latency when speaking in context of comparable latency?!

Thankfully, I know exactly where the bodies are buried regards how that correlates to actual I/O and RTL with Dante, and what is actually delivered through extensive testing and qualification over numerous configurations. I don’t have the same hands on with AVB unfortunately, so I take their claim of 2ms with more than a few grains, as I have no context of what those figures translate to regards delivered working latencies. AVB is not as widely marketed or adopted for studio usage, the only exception that comes to mind is AVID’s Carbon interface.

With AVB having no native support for Windows, my experience and testing is at zero, but my understanding is that it is very particular with switches that are used in the configuration of the devices to the computer system. The switches are needing to be AVB qualified, whereas with Dante, any good quality Ethernet switch can be used. But that was not always the case, where my early explorations of Dante powered systems was far less straight forward, requiring managed switches. That has been resolved over the years to allow a simpler and cheaper switching option.

AoIP, just give me the numbers thanks !

So from here on I will focus only on my direct experience and testing, which has been with Focusrite RedNet, using the respective matching RedNet PCIe accelerator card in combination with an I/O, and also RME’s Digiface Dante implementation, where they combine the Audinate Controller with their FPGA/USB3 Driver/TotalMix implementation. I have the results for both the Focusrite RedNet I/O & DSP Card, and the RME USB3/Focusrite RedNet combinations listed in the Database. Both performed well and very close to each other in overall I/O, RTL and driver performance. I must admit I had some initial hurdles for me in getting my head around the Dante configuration, but once navigated, it was reasonably straight forward. The later combination of the RME with the RedNet highlighted one major advantage of Dante over AVB, and that is compatibility across products from different manufacturers is guaranteed. The same cannot be said with AVB, from my understanding from the information I have gathered.

O.K, that brings us up to speed and up to date re the available protocols to 2025.

LLP ( Low Latency Performance ) Rating : What and How ?

The real question when it comes to low latency performance is not what buffer settings are available in any respective interface control panel , but whether the available settings are actually usable in Real World working environments.

The delivered I/O and RTL has little relevance if the driver is inefficient at the preferred latencies, it is simply a number that can be quoted and bandied around, but is irrelevant when dealing with the actual end user experience if you cannot realistically use those lowest buffer settings. A perfect example ( and lets remove the 064/128/256 window dressings ) , some interfaces need 9+ ms of playback latency to perform equally to others at 4 ms in respect to number of plugins/polyphony on the benchmarks , this is the reality of the actual overall performance. This has nothing to do with delivered I/O and RTL latency, it is purely the efficiency of the driver evidenced by the fact that it takes more than double the playback latency to deliver equal performance of a better performing driver. Latency performance is more than just input monitoring / live playing.

Here is where I will insert what has become my mantra for the last 14 years.

“I/O and RTL is only ½ the equation , the other ½ which is equal if not more important is the efficiency and stability of the driver at the respective latencies when placed under load”

With that in mind I decided to develop a rating system that takes into account numerous variables relevant to overall low latency performance. An explanation of how the LLP- Low Latency Performance Rating is derived is as follows.

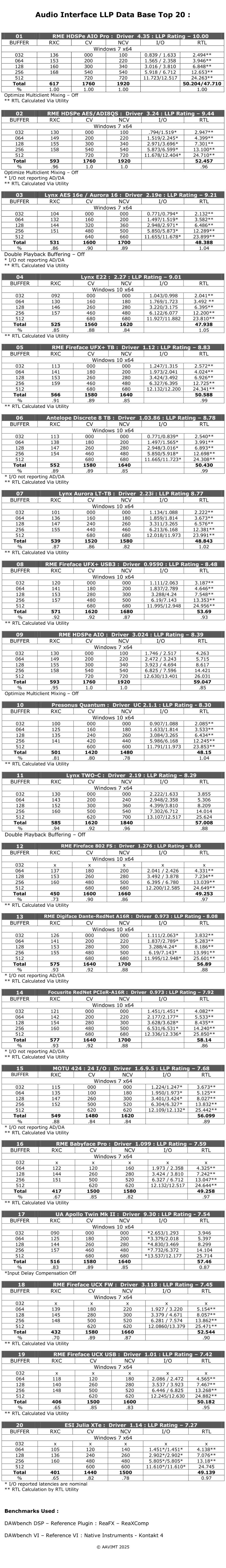

3 reference benchmarks are used - DAWbench DSP - RXC , and 2 variations of the DAWbench VI benchmark CV ( utilizing convolution verbs) and NCV ( no convolution verbs)

The results for the DAWbench DSP RXC across the latencies of 032 thru to 256 ( which has been the M.O for the last 14 years ) are added and the total is then % wise gauged against the result for the RME HDSPe baseline card. The same is then calculated for the DAWbench VI CV/ NCV tests for 032-512.

Those 3 % results are then added and divided by 3 to give an average % .

I thought it important for the I/O and RTL figures to be an influencing factor on the rating as some cards have a lot lower overall latency than others, so the average % results is then multiplied by the last % result for the RTL.

How the RTL % is calculated is I combine the total of the RTL values across the specific available buffer settings for the cards. There are 2 default values listed for RTL for the RME HDSPe baseline , first being for 032-512, second being 064-512 , the appropriate value being used depending on the respective test cards range of available latencies.

In the instance that the test interface has a different range of latency values available- i.e. 128-512 , then calculations are adjusted accordingly from the appropriate values of the base reference interface.

I then calculate the % variable against the baseline.

To summarize, the average % value across the 3 benchmarks is multiplied by the RTL% value to give the final rating.

I think that is a fair appraisal using the collated data, and it gives deserved credit and advantage to those cards that do have lower individual In/Out and Round Trip Latencies.

All testing from the the beginning has been on the same 2 reference systems, one being the original Windows 7 system that is not really used now except as a cross reference for early results if need be. The later is a Windows 10 system that has been core/clock limited to match the original system, and results are corrected % wise after being cross referenced against the original vs later architecture. The later system has the addition of Thunderbolt and a current build of W10 for driver support. I have locked down and maintained these systems all these years as an empirical constant to ensure the comparative accuracy of the newer tested interfaces against those already archived in the database. Yes the systems are of older architecture, but they are only there as control parameters to maintain the integrity of the database.

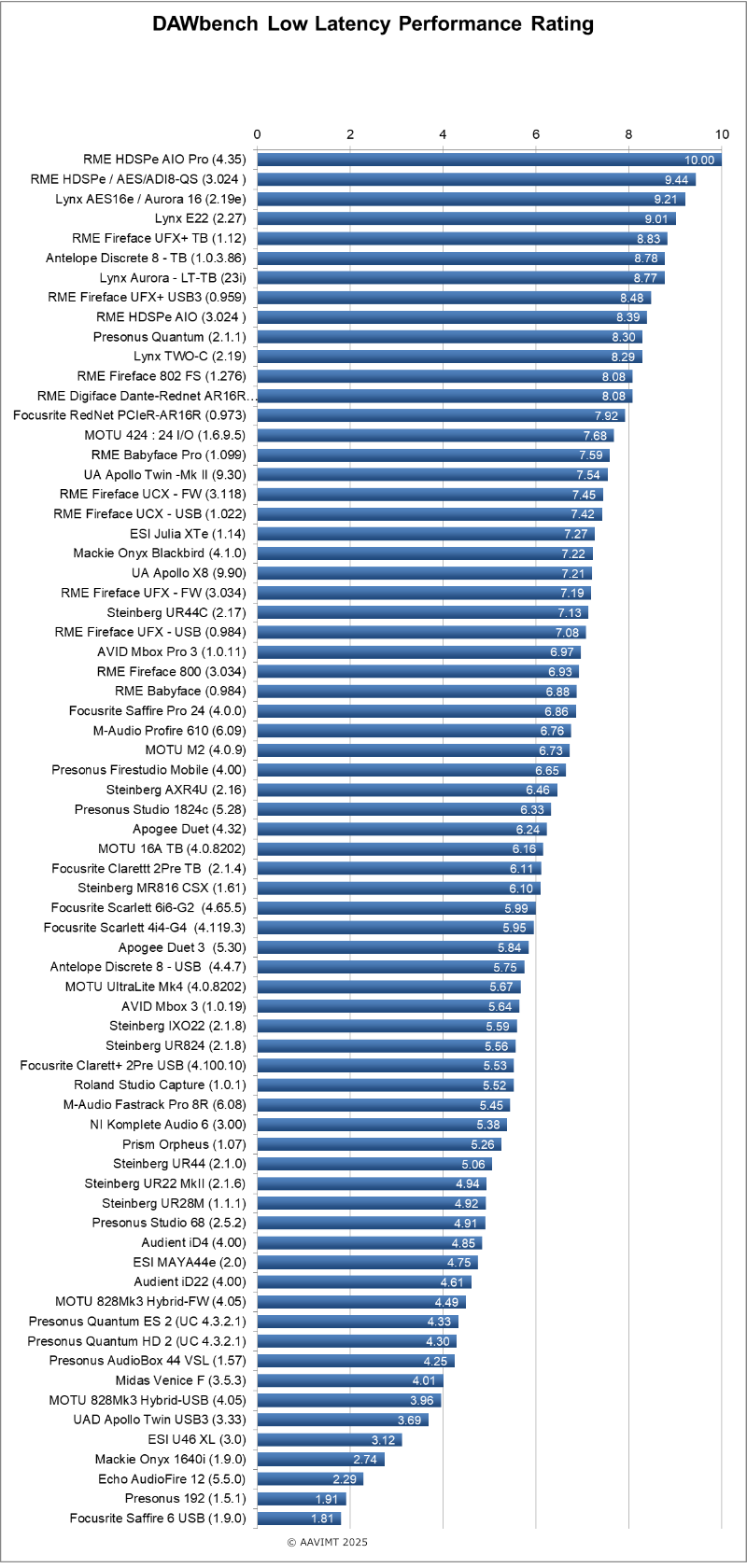

The charts below give a clearer indication of what I have outlined with the detailed results for each respective interface.

Getting into the Details and Navigating the Curves

Top 20 and Full Database updated September 2025

Full Database of over 60 interfaces can be viewed and downloaded Here

The results charts clearly show that there are huge variables in not only the dedicated I/O Latency and RTL, but also the overall performance at the respective buffer settings. Its not as simple as comparing performance results at any given dedicated control panel buffer setting when there are such large variables in play - i.e. RTL for buffer settings of 064 range from under 4ms to over 12ms as I noted earlier.

Its also not as clear cut as saying that for example FW interfaces offer better performance than USB 2.0 or vise versa , as there are instances of respective interfaces clearly outperforming others using the various protocols.

The tested PCI/PCIe interfaces do however still lead in performance , clearly indicated by the tables above , but the variance is not as large as it once was. The better TB and USB3 interfaces for example are not too far off the base reference in performance, I/O and RTL.

Its also worth repeating and noting that numerous manufacturers continue utilizing not only the identical controllers but also the bundled OEM driver, which for the most part is convenient for them to get products to market, but the products using the above cover a large end user demographic, and the drivers are not necessarily the best catch all for more demanding working environments.

Whereas they will be fine for live tracking and in session environments focussing on audio where low latencies are not a priority , once the latencies are dialed down for live Virtual Instrument playing / Guitar Amp Simulators for example, the performance variable at those lower /moderate latencies can be in the vicinity of 40+%. That is a huge loss of potential overhead on any DAW system.

Conclusion and Final Thoughts.

What I have learned over the course of the last 14 years of sharing my R&D publicly is that Low Latency Performance is something that is still not very well understood by a large section of the end users, and some marketing departments are all too happy to continue to blur the lines when talking about interface latency performance.

A few typical methods in regards to marketing, one tactic is to list latency values only at higher sample rates like 96K for a lower latency number, which is fine if you are working at that sample rate. I find most will work at 44.1K/48K, which are used more commonly for music / and music for film/TV respectively. Another is to market the interfaces with good Low Latency Monitoring, but they are specifically referring to monitoring thru a DSP/Hardware Mixer Applet / ASIO Direct Monitoring - which is essentially the latency of the AD/DA + a few added samples for arbitration to/from the DSP/FPGA. Are they specifically marketing the interface in a false manner, of course not , as many interfaces now have a good hardware onboard mixing facility, so direct monitoring sans FX is essentially real time. This however has been available since the late 90's on Windows and isn't anything particularly new or anything to be hyping about IMO.

Where it gets murkier is when we are dealing with I/O and RTL latencies monitoring thru FX and/or real time playing Virtual instruments, as that is when the efficiency of the controllers/ drivers come into play. Further to that, the actual scaling performance of the above at the respective working latencies is an area that has huge variables as I noted earlier. Now to be clear, I am focussing purely on the area of Low Latency Performance for those needing that facility when using Guitar Amp Simulators and Virtual Instruments. For those needing basic low latency hardware monitoring for tracking audio and have minimal focus on larger FX/MIDI/Virtual Instrument environments , then its not as much as a priority.

If the drivers are stable at any given working latency that allows the end user to track and mix with minimal interruption, then all well and good. The question then is - how many manufacturers using the lesser performing controller/driver options specify the preferred working environments that their interfaces will be best suited ?

We already know the answer to that.

I have come to understand and accept that this is an area that some manufacturers and their representatives are not overly happy about having an added focus on. I have had numerous encounters with certain developers and manufacturers over the last 14 years who seem confused if not clueless in regards to the whole area of LLP that I have presented, and continue to deliver products on to the market with a narrower focus of the actual end user requirements. I understand that this can be very sensitive and even confronting especially if the developer is being challenged about a poorly performing driver. Having said that, I would think it was in their best interest to remain open and communicative, especially when time and energy is being offered to help and improve the driver. I also understand that some do not have the direct resources at their disposal regards I.P or driver development, or their R&D has lead them to a position that is not easily remedied, but there are direct benefits to all involved when better performing drivers are able to be delivered to the end users. My aim in shining a light on this area of driver performance, has always been and remains to bring attention to the manufacturers who do make the extra effort , and are duly rewarded.

If you have any further questions on the information in the article, feel free to reach out via socials or email.

Can not thank you enough for your invaluable work. Dawbench has become a staple of every serious discussion about system performance. The credibility amassed by all the work has proven precious for all those seeking answers about creating a fully working and efficient workstation. Thank you.